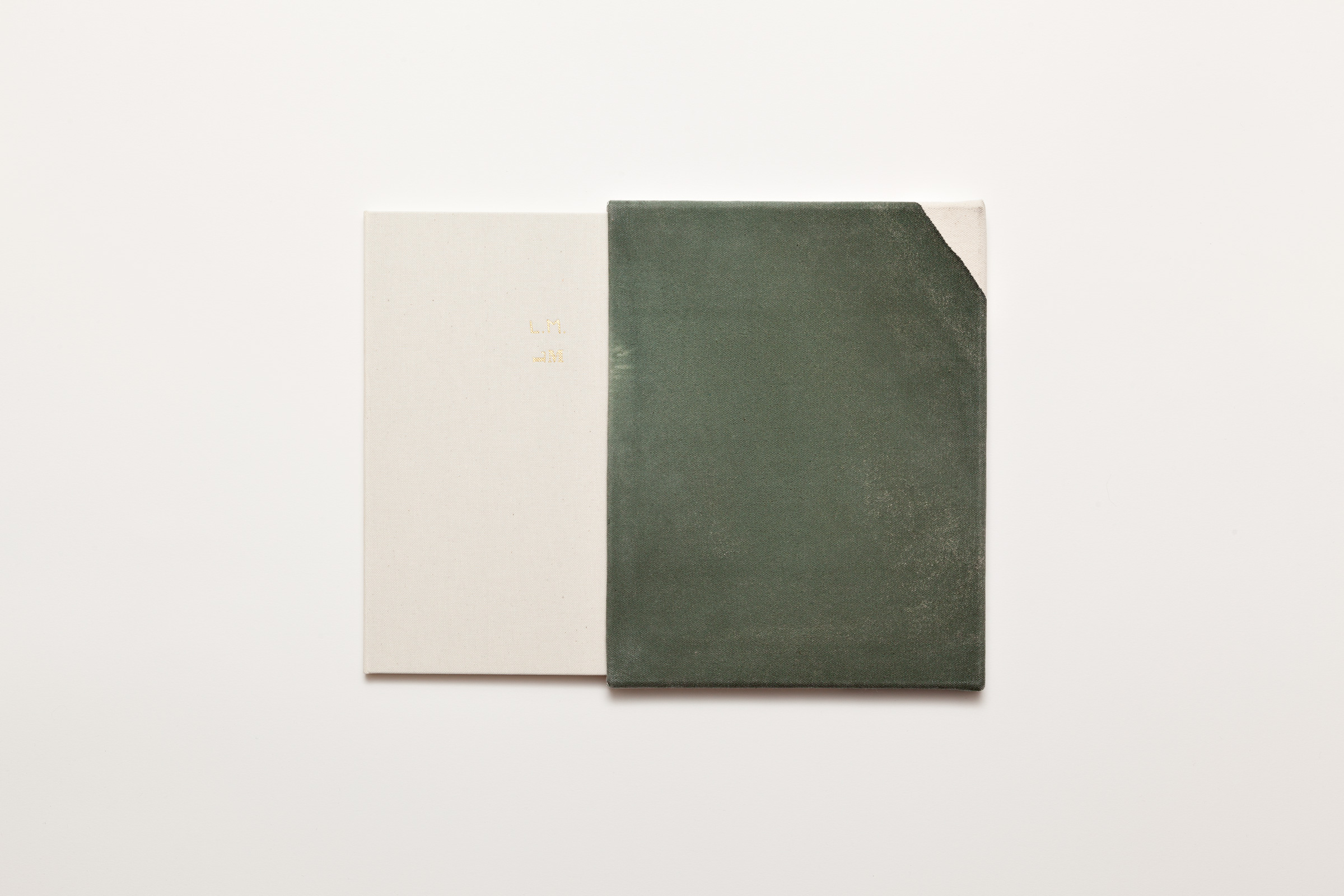

23 x 29 cm. 32 pages. 24 color plates. Offset printed clothbound hardcover. Linen thread bound. Swiss binding. Cover text in gold foil.

ISBN 978–91–86269–29–6

Published in 2014.

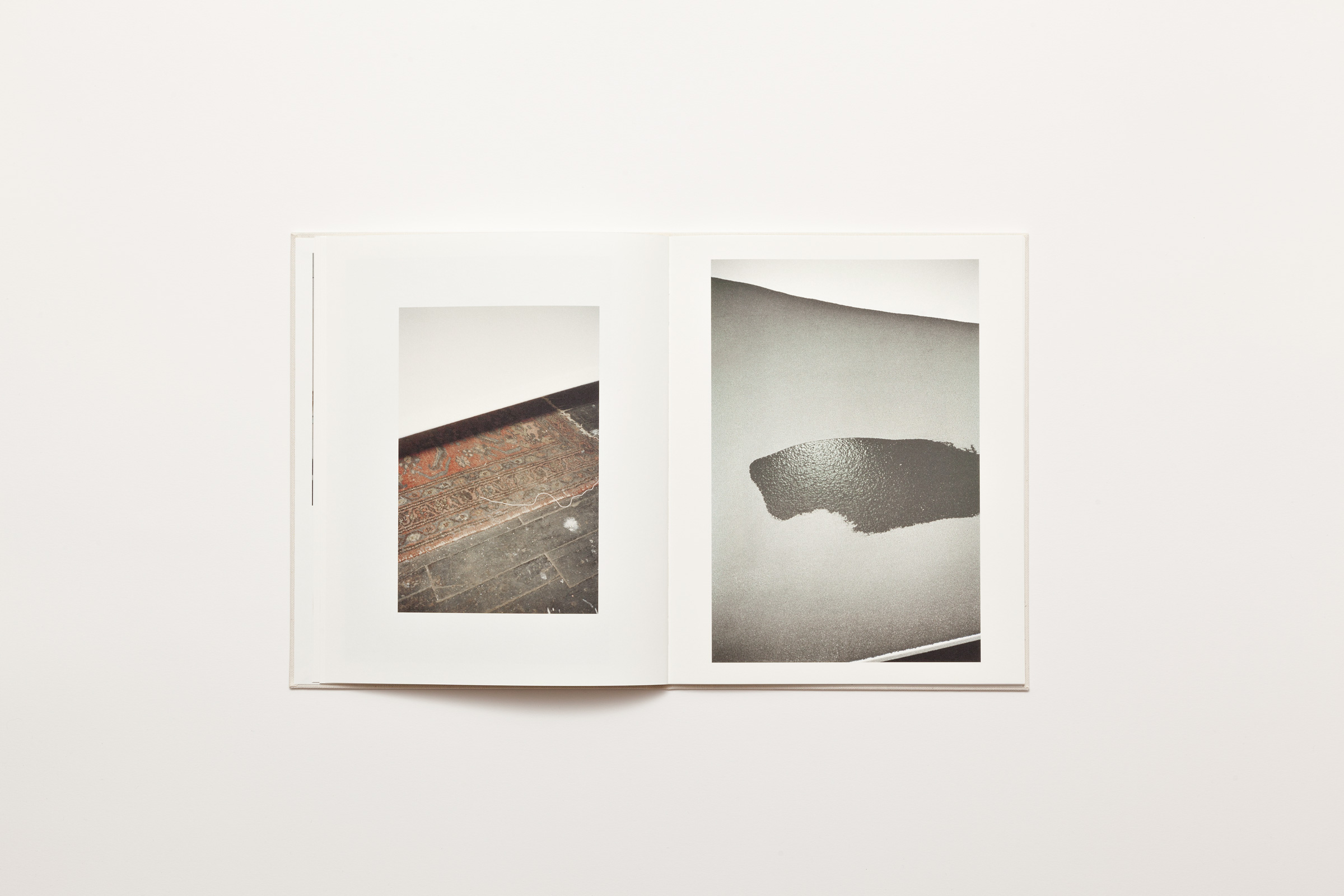

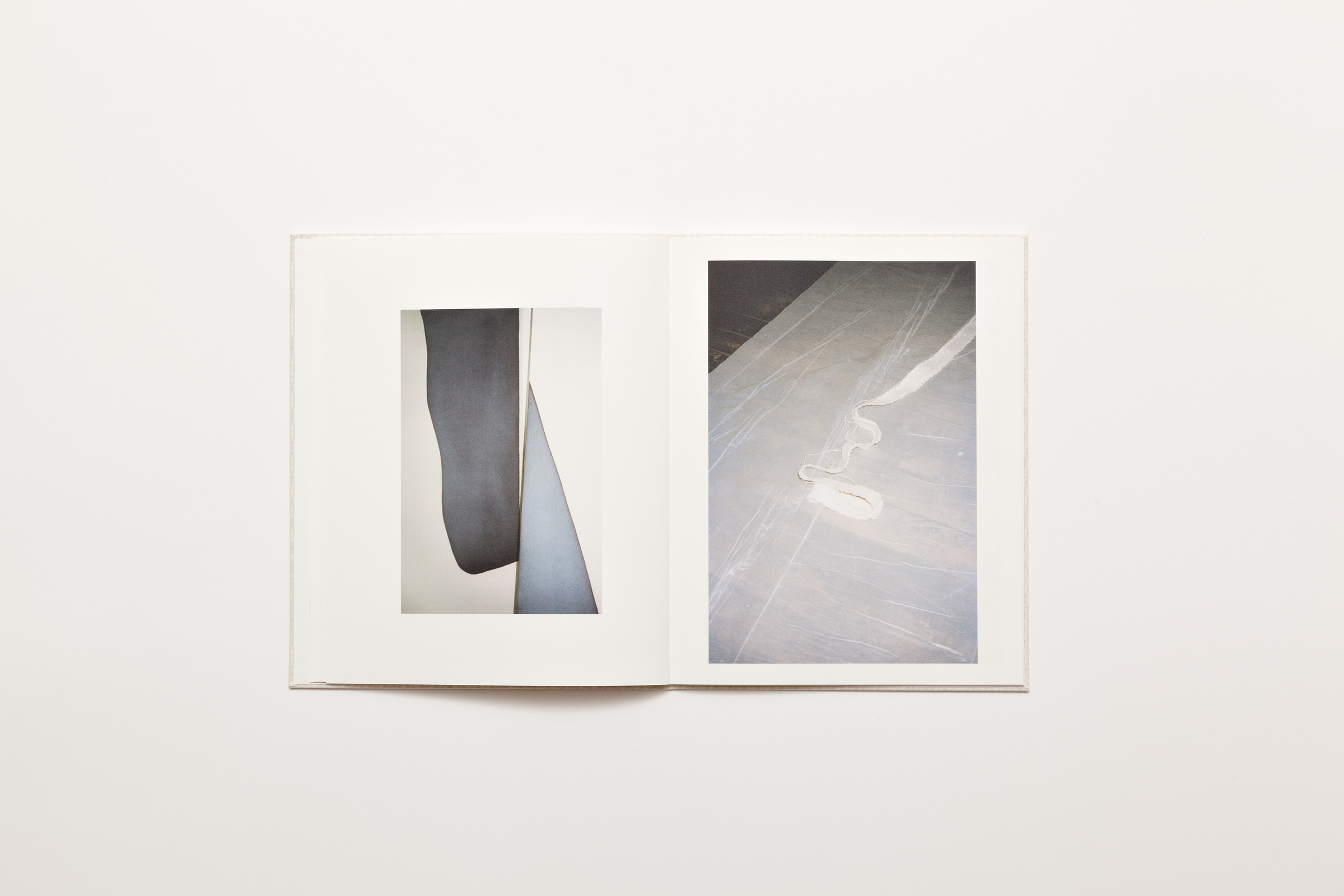

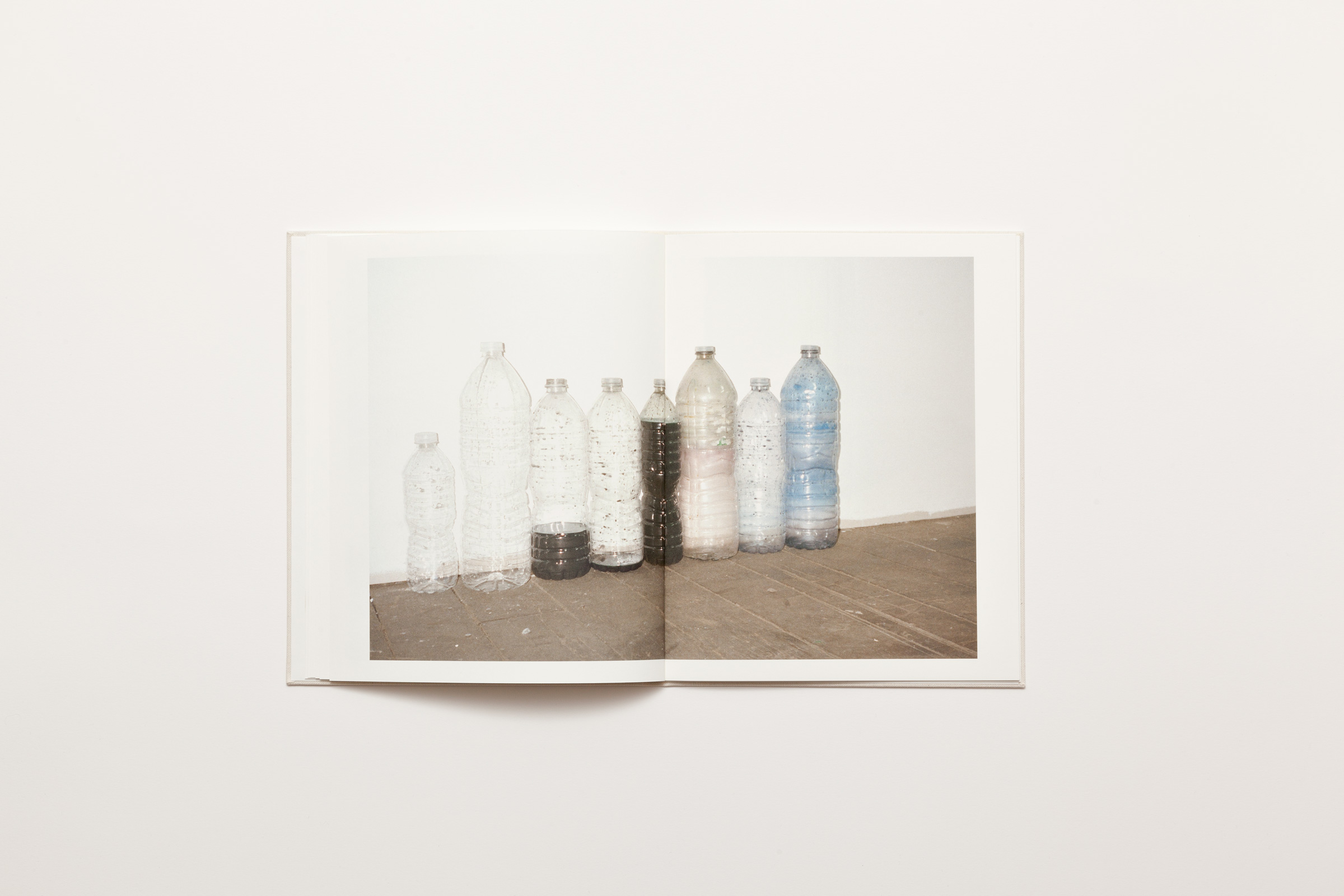

In preparing for solo exhibition Michael Jackson Penthouse at Retrospective Gallery, American artist Landon Metz (b. 1985, American) was commissioned to portray his work process in his New York based West Street Studio through a camera lens, for two intensive weeks. The limited edition photo-book is unique in its kind as the art form differs from that of the artist's signature.

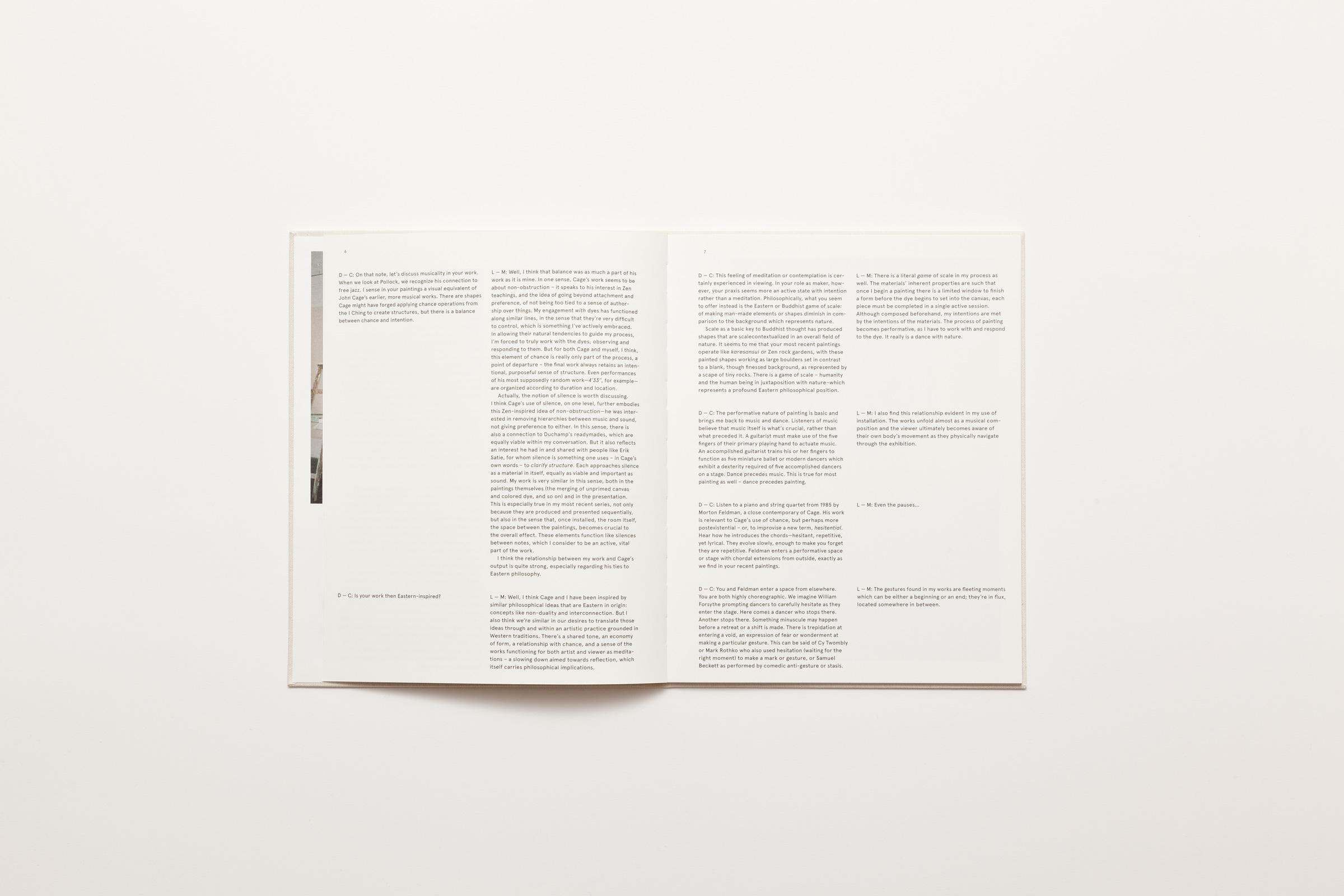

The book contains a 4-paged conversation between Landon Metz and American art curator Diego Cortez, as well as a poem written by the author.

First edition of 400 copies, numbered. Special edition of 25 copies, numbered, in unique monochrome hand-painted canvas slipcase with signed woodblock print.

→ A conversation between Landon Metz and Diego Cortez, May 10, 2014 — New York

Diego Cortez — I find in your work plays at the cusp between reality and imagination. This is the happiest zone of engagement – an interzone of both creativity and philosophical enlightenment, with each element informing and enhancing the other.

Landon Metz — Definitely. I don’t believe in absolutes. I feel that the intellectual experience of art doesn’t inherently oppose its aesthetic experience, and that an artwork’s visual attributes might embody its content rather than signify it. Without useless hierarchies, the illusory separation of opposing poles dissolves. I’m constantly looking inward through my practice to discover new forms of expressing this sense of interconnectedness.

Just as the world is relative to individual experience, art’s meaning is relative to its viewers’ experience and, ultimately, outside the artist’s control. Duchamp’s work speaks to the idea that art doesn’t lie in the artist’s intentions, or even in the work itself, but rather in the viewer’s perception. In that same spirit, I intentionally enfranchise the viewer, allowing them space for both entry and interpretation. At best, I can hope only to use my work to allude to the philosophical current that runs through my practice.

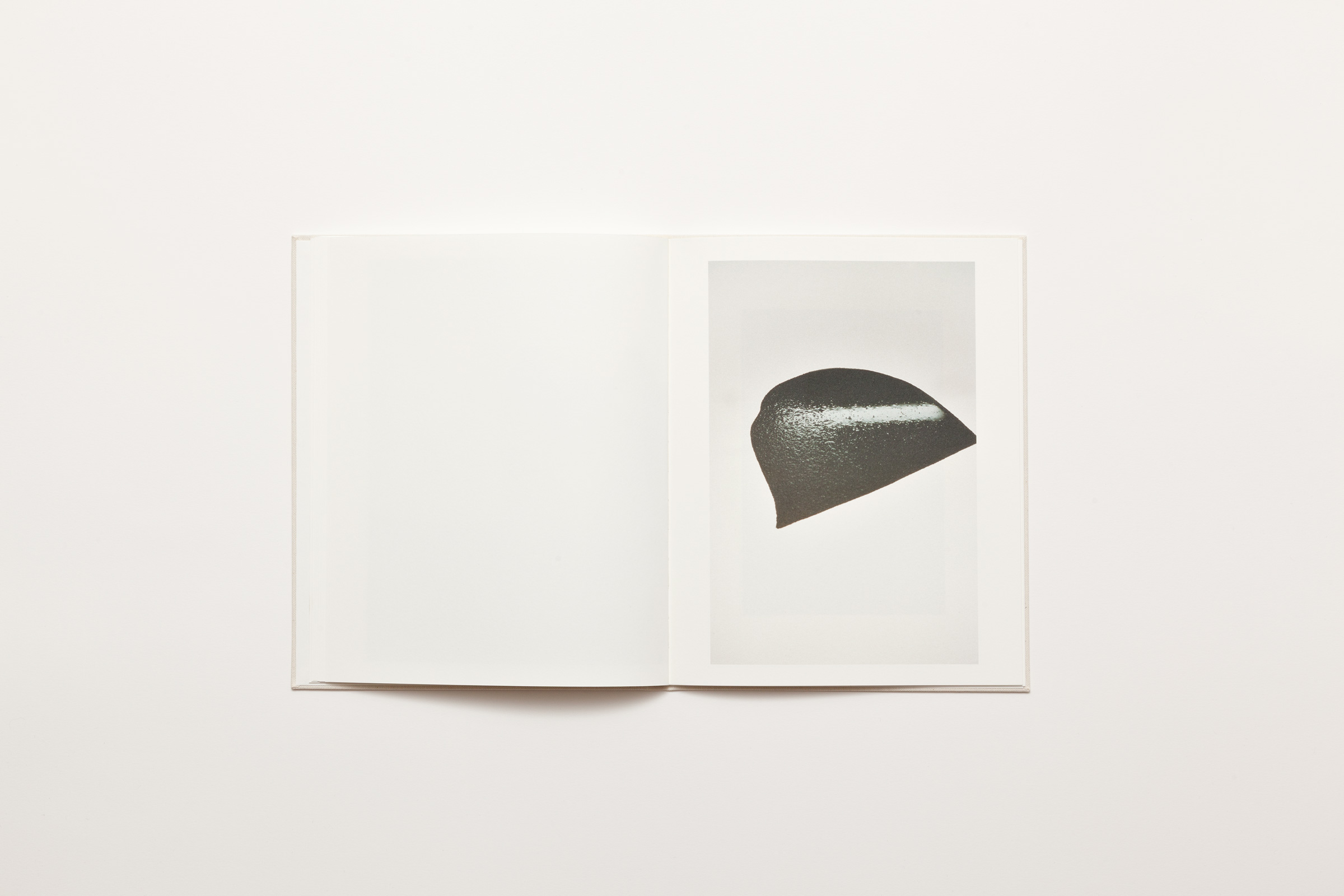

For example, the decision to use dyes was to establish greater physical interconnection, as dye, unlike paint, actually merges with its supporting surface, maintaining a homogeneous textural field. The picture maintains an awareness of and reverence for picture plane surface and objecthood – as well as the resulting space and viewer.

I want each component of the artistic process – my relationship to the materials, the work’s relationship with the viewer, and so on – to become intimate and reciprocal.

Cortez — In that same sense, your new works seem to reference the moment when color field predicts the lyrical wing of a later minimalist art. They are lyrical, but still minimal.

Metz — Although there are fundamental differences between us, I do share some central concerns with the color field artists: the integration of medium and support, the emphasis on literal surfaces over illusory depth, and an interest in imbuing the subtleties of watercolor with the authority of larger ab-ex canvases – or, perhaps more pointedly, in using the scale of those canvases in a more subtle, sensitive way. But the comparison ends there, because I ultimately view painting as a tool to communicate ideas – I’m not interested in resolving the historical baggage the medium carries, but rather in using it as a philosophical vehicle. With minimalism, I think my work shares an emphasis on simplicity; I try not to introduce any elements into my paintings – into my overall practice, really – that don’t need to be there, that don’t serve a very particular function. In terms of visual artists, I’ve always related to people like Agnes Martin and Carl Andre – regardless of scale, their work always conveys an underlying sense of quietude without ever being reticent. I also feel connected to minimalist composers like Steve Reich and Terry Riley – their embracement of repetition and loops, and how they allow simple forms and patterns to overlap, interconnect, and build towards something much larger and more complex.

Cortez — On that note, let’s discuss musicality in your work. When we look at Pollock, we recognize his connection to free jazz. I sense in your paintings a visual equivalent of John Cage’s earlier, more musical works. There are shapes Cage might have forged applying chance operations from the I Ching to create structures, but there is a balance between chance and intention.

Metz — Well, I think that balance was as much a part of his work as it is mine. In one sense, Cage’s work seems to be about non-obstruction – it speaks to his interest in Zen teachings, and the idea of going beyond attachment and preference, of not being too tied to a sense of authorship over things. My engagement with dyes has functioned along similar lines, in the sense that they’re very difficult to control, which is something I’ve actively embraced.

In allowing their natural tendencies to guide my process, I’m forced to truly work with the dyes, observing and responding to them. But for both Cage and myself, I think, this element of chance is really only part of the process, a point of departure – the final work always retains an intentional, purposeful sense of structure. Even performances of his most supposedly random work—4’33”, for example—are organized according to duration and location.

Actually, the notion of silence is worth discussing. I think Cage’s use of silence, on one level, further embodies this Zen-inspired idea of non-obstruction—he was interested in removing hierarchies between music and sound, not giving preference to either. In this sense, there is also a connection to Duchamp’s readymades, which are equally viable within my conversation. But it also reflects an interest he had in and shared with people like Erik Satie, for whom silence is something one uses – in Cage’s own words – to clarify structure. Each approaches silence as a material in itself, equally as viable and important as sound. My work is very similar in this sense, both in the paintings themselves (the merging of unprimed canvas and colored dye, and so on) and in the presentation.

This is especially true in my most recent series, not only because they are produced and presented sequentially, but also in the sense that, once installed, the room itself, the space between the paintings, becomes crucial to the overall effect. These elements function like silences between notes, which I consider to be an active, vital part of the work.

I think the relationship between my work and Cage’s output is quite strong, especially regarding his ties to Eastern philosophy.

Cortez — Is your work then Eastern-inspired?

Metz — Well, I think Cage and I have been inspired by similar philosophical ideas that are Eastern in origin: concepts like non-duality and interconnection. But I also think we’re similar in our desires to translate those ideas through and within an artistic practice grounded in Western traditions. There’s a shared tone, an economy of form, a relationship with chance, and a sense of the works functioning for both artist and viewer as meditations – a slowing down aimed towards reflection, which itself carries philosophical implications.

Cortez — This feeling of meditation or contemplation is certainly experienced in viewing. In your role as maker, however, your praxis seems more an active state with intention rather than a meditation. Philosophically, what you seem to offer instead is the Eastern or Buddhist game of scale: of making man-made elements or shapes diminish in comparison to the background which represents nature.

Scale as a basic key to Buddhist thought has produced shapes that are scalecontextualized in an overall field of nature. It seems to me that your most recent paintings operate like karesansui or Zen rock gardens, with these painted shapes working as large boulders set in contrast to a blank, though finessed background, as represented by a scape of tiny rocks. There is a game of scale – humanity and the human being in juxtaposition with nature–which represents a profound Eastern philosophical position.

Metz — There is a literal game of scale in my process as well. The materials’ inherent properties are such that once I begin a painting there is a limited window to finish a form before the dye begins to set into the canvas, each piece must be completed in a single active session. Although composed beforehand, my intentions are met by the intentions of the materials. The process of painting becomes performative, as I have to work with and respond to the dye. It really is a dance with nature.

Cortez — The performative nature of painting is basic and brings me back to music and dance. Listeners of music believe that music itself is what’s crucial, rather than what preceded it. A guitarist must make use of the five fingers of their primary playing hand to actuate music. An accomplished guitarist trains his or her fingers to function as five miniature ballet or modern dancers which exhibit a dexterity required of five accomplished dancers on a stage. Dance precedes music. This is true for most painting as well – dance precedes painting.

Metz — I also find this relationship evident in my use of installation. The works unfold almost as a musical composition and the viewer ultimately becomes aware of their own body’s movement as they physically navigate through the exhibition.

Cortez — Listen to a piano and string quartet from 1985 by Morton Feldman, a close contemporary of Cage. His work is relevant to Cage’s use of chance, but perhaps more postexistential – or, to improvise a new term, hesitential. Hear how he introduces the chords—hesitant, repetitive, yet lyrical. They evolve slowly, enough to make you forget they are repetitive. Feldman enters a performative space or stage with chordal extensions from outside, exactly as we find in your recent paintings.

Metz — Even the pauses…

Cortez — You and Feldman enter a space from elsewhere. You are both highly choreographic. We imagine William Forsythe prompting dancers to carefully hesitate as they enter the stage. Here comes a dancer who stops there. Another stops there. Something minuscule may happen before a retreat or a shift is made. There is trepidation at entering a void, an expression of fear or wonderment at making a particular gesture. This can be said of Cy Twombly or Mark Rothko who also used hesitation (waiting for the right moment) to make a mark or gesture, or Samuel Beckett as performed by comedic anti-gesture or stasis.

Metz — The gestures found in my works are fleeting moments which can be either a beginning or an end; they’re in flux, located somewhere in between.

€52

First edition

€400

Special edition